Alugha Updates | March 2022 - what's new at alugha

Here at alugha, we love technology and leveraging it in creative ways for our users to provide unique features and a stellar experience.

The Portuguese language, spoken by more than 200 million people around the world, has often been described as the “fatherland” or “motherland” of the Portuguese-speaking world.

Read this article in: Deutsch, English, Español, Português

Estimated reading time:5minutesOn February 21 we commemorated International Mother Language Day, established by UNESCO in 1999. In a tribute to the Portuguese language in all its linguistic and cultural diversity, we invite you in this article to navigate through reflections from Portuguese-speaking bloggers, prompted by their reading of the first novel dedicated to the Portuguese language [pt], Milagrário Pessoal – the most recent work by the Angolan author José Eduardo Agualusa.

The title of this article was taken [pt] from the blog Mértola, in which Carlos Viegas writes that Milagrário Pessoal is:

a declaration of love to the Portuguese language, in all its variations (…) a journey through the history of our language, through the places and cultures which feed its great richness.

Portuguese is the official language of eight countries – Angola, Brazil, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique, Portugal, São Tomé and Príncipe and East Timor – in four continents – Africa, America, Asia and Europe. Thus, the language covers a vast area of the Earth's surface (7.2% of the planet [pt]), encompassing an extraordinary diversity of lives which is reflected in the variety of dialects. It is also the fifth most spoken language on the Internet, according to Internet World Stats, with around 82.5 million internet users. Deceased in June 2010, José Saramago – the only Portuguese-speaking winner of the Nobel prize for Literature – said that “there is no Portuguese language, but rather languages in Portuguese ” [pt]. The writer Agualusa, in an interview [pt] with the blog Porta-Livros, states that:

The Portuguese language is a combination of all the people who speak Portuguese and it is this which makes it such an interesting language, with such great elegance, elasticity and plasticity.

The novel – or the “essay on the Portuguese language disguised as a novel”, as the journalist Pedro Mexia describes it in a critique entitled Politics of Language [pt] – simultaneously tells a love story and explores the processes of construction of the Portuguese language. Agualusa, again in the afore-mentioned interview, confesses to “greatly regretting the disappearance of certain beautiful words which fall out of usage” and shares the necessity and “obligation to prevent the death of these words”.

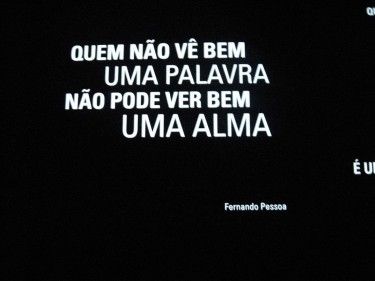

Poem by Fernando Pessoa: He who cannot fully perceive a word, can never fully perceive a soul. Photo: Lu Freitas on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

Rui Azeredo, from the blog Porta-Livros, explains [pt] that the “[love] story serves solely as a pretext for the author to pay homage to the Portuguese language” :

through a search by the novel's main characters for Portuguese neologisms. And neatly embedded in the middle of the story (…) we find the neologisms, as if in a lesson we don't even notice, but in which we learn everything. From Portugal to Angola, via Brazil and other countries, our eyes run over word games (both new and old, depending at times on the geographical situation) cleverly thrown in by Agualusa.

In a summary [pt] of Milagrário Pessoal, Bruno Vieira Amaral, from the blog Circo da Lama, considers that “words have power, words are power”. Amaral comments on excerpts from Milagrário Pessoal - in quotes as fanciful as they are representative of the countries to which they refer – in which the Portuguese language serves as a vehicule for refractory, subversive and nationalist political practices:

Words are also power, politics in the broadest sense. They can reflect disobedience, as in the case of the Timorian who recited sonnets from Camões. They can reflect nationalist affirmations, as in the case of the Brazilian elites who began to use nicknames of Tupi origin. They can reflect subversion, like the colonised who seek to colonise the language of the coloniser in order to dominate him.

José Leitão, in the blog Inclusão e Cidadania, supports this view [pt]

The novel contains precious clues for a policy on language, which deserve the attention of social scientists, linguists and those responsible for policy relating to the Portuguese language.

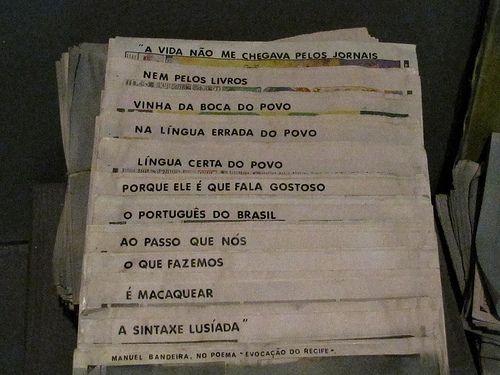

Poem by Manuel Bandeira: Life did not come to me through newspapers nor through books/It came from the mouth of the people in the incorrect language of the people/Correct language of the people/Because it is the people who delight in speaking the Portuguese of Brazil/While in the meantime/What we are doing/Is mimic/The Portuguese syntax. Photo by Capitu on Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The reflections of Milagrário Pessoal‘s readers in the blogosphere at times broach the subject of the controversial Spelling Reform of the Portuguese language, which aims to unify and converge the different spellings used in each Portuguese-speaking country. In his interview with the blog Porta-Livros, Agualusa states:

Never before has there been such a degree of movement of people and ideas between Portuguese-speaking countries. (…) And this means that the language comes closer together.

Pedro Teixeira Neves, of PNETLiteratura, quotes [pt] a passage from the book and asks:

“Moisés da Conceição writes that the Portuguese language, African in its matrix as a result of its prolonged cohabitation with Arabic which influenced it greatly, needs to darken still further, moulding itself to the geography of the places inhabited by its abundance of speakers. Our destiny is to swallow one another up…”. In summary, this is in some way the underlying thesis upon which the fictional side of this novel is overlaid. Concealed criticism of the spelling reform? Why not read between the lines in this manner?…

Offering no response to his question, Teixeira Neves states that “language is a treasure” [pt] and concludes:

A treasure held not in a chest sealed from the peoples who use it (thus, who speak this language, or Portuguese), but a treasure which in its geographic diversity and continual growth becomes richer and broader. In short: the language has multiple identities, and this fact can only represent an addition, never a subtraction. Language is elastic, a living body which feeds off time and times. Language is a continual voyage through oceans never before seen or sailed.

Paula Góes contributed to the illustration of this article. All photos were taken from the Museum of the Portuguese Language, in São Paulo, Brazil.

Written by Sara Moreira. On globalvoices.org.

Here at alugha, we love technology and leveraging it in creative ways for our users to provide unique features and a stellar experience.

Here at alugha, we love technology and leveraging it in creative ways for our users to provide unique features and a stellar experience.

“Management is the art of orchestrating best possible collaboration in an organization.” Where this “art” (for me) combines both, the willingness and the ability to act. Both have to be reflected in the two main areas of management: in the function “management” (the “how” and “what”) and the instit

Alugha is a video translation tool that streamlines the production and collaboration process for high-quality content tailored to international audiences. Learn more at: https://appsumo.8odi.net/get-the-starter-pack You’re ready to share your videos with the whole wide world. But like a certain co

IZO™ Cloud Command provides the single-pane-of-glass for all the underlying IT resources (On-premise systems, Private Cloud, Cloud Storage, Disaster Recovery, Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, Google Cloud Platform, etc). About Tata Communications: Welcome to Tata Communications, a digital ecos

A revolutionary new service in the video industry! Our report is about the unique alugha platform. Alugha gives you the tools to make your videos multilingual and provide them in the language of your viewers. Learn more about the great features of the platform here: https://alugha.com/?mtm_campaign